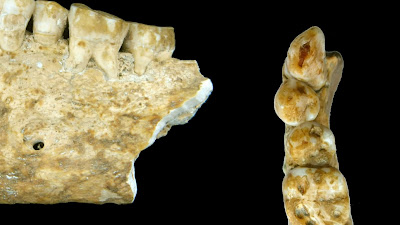

Around 300,000 years ago, the homo rhodesiensis species showed signs of extreme wear on their teeth. Their tuff diet and near-chronic abscesses were just one step on the long road from dental evolution to modern humans. But it would take a few hundred thousand years for dentists to appear. Around 7000 BC. With the civilization of the Indus Valley, we begin to see some of the first evidence of early dentists practising their profession. This comes in the form of holes drilled in the teeth, presumably to remove cavities/decay. This drilling technology most likely came in the form of the bow drill, a fairly crude mechanical tool, but effective nonetheless. It is thought that bead making was the primary occupation of these early dentists who probably made house calls, although this was probably not a pleasant experience.

Around 5000 BC in southern Mesopotamia, the Sumerians wrote down a key concept related to teeth. There is a text describing the cause of toothache and tooth decay. They believe such things happened because of the tooth worm. The tooth worm was taken very seriously. Around 700 BC. In the Assyrian city of Nineveh, possibly suffering from a toothache, wrote an invocation against the tooth worm. It deplores the nature of the worms and begs the gods to strike it down. The concept of the tooth worm was widely accepted until the early 18th century. Practitioners would even yank at nerves thinking them worms until the idea was challenged by Pierre Fauchard, we’ll get back to him.

They developed early recipes for toothpaste that crushed burnt oxen hooves, eggshells, and myrrh, and even used opium as a pain reliever. However, they also believed that touching an aching tooth with a dead mouse could cure pain. Some evidence for ancient dentistry is indirect. Around 1800 BC, King Hammurabi’s code states that bad physicians and dentists can be punished by having a hand removed. In Italy in the 8th century BC, before Rome really started roaming, the Etruscans flourished. This fascinating Iron Age culture developed false teeth using human or animal teeth held together with gold bands. And similar appliances held loose teeth in place.

As early as the 5th century BC in ancient Greece, Hippocrates himself wrote about the treatment of decaying teeth and gum disease. Greek physicians also extracted teeth and used wire to stabilize teeth. In the early first century AD, Rome gained its first emperors and it is about this time, but the Roman physician Celsus was writing that he was the first to describe a lead filling in a cavity. But this was only to stabilize fragmented teeth for extraction. Around 15 AD, a Greek physician working in Rome Arkigenise suggested to drill out tooth decay and fill it with roasted earthworms and the crushed eggs of spiders. The Romans gave dentistry its patron Saint Apollonia. In 249 AD she was martyred in Alexandria, all her teeth were forcibly pulled. This relic from Portugal supposedly contains one of those teeth.

What about the Saxons and Vikings of the latter first millennium AD in northern Europe? Well, contrary to popular imagery, they tended to have very good teeth. This is due to a relative lack of sugar in their diets. Although a Viking skull found in 2009 in Dorset has grooves filed into his two front teeth, probably to add to the ferocity of its appearance.

Around the same time in China during the Tang Dynasty, they probably developed the first toothbrushes using hog bristles. And in 1223, the Japanese Zen master Dogen recorded that he saw monks in China clean their teeth with brushes made from horsetail hair attached to an ox bone handle. And it would be 1690 centuries before Anthony Wood buy a toothbrush in Europe. In the intervening years during the early Middle Ages in Europe, sciences such as medicine, surgery, and dentistry were generally practised by monks. However, a series of 12th-century papal edicts expressly prohibited monks from performing any form of surgery. So dental care was no longer the purview of educated monks, but rather their less-educated assistants (the people who shaved the heads of monks). Barber surgeons were let loose on the public performing extractions.

Just at the time when sugar was becoming increasingly popular in Europe, the great medieval surgeon Abu al-Qasim al Zawahri inspired European surgeons and in the 14th-century people like the celiac guide invented the dental pelican. Resembling the beaks of a pelican, dentists still use a similar tool for extractions today. Dental care at that time was highly dependent on status in society. Barber surgeons continue to practice among the lower classes and try to stick with extractions and attempts to relieve pain.

In the 16th century, dental care has changed little. A Tudor dentist would be a painful experience. According to the Tudor dentist, boiled frogs were a staple and foul concoctions were applied to rotten teeth to encourage them to fall out. There was an attempt to clean using frayed tea twigs that would be rubbed on the teeth with a paste made from rose water, lavender, and cuttlefish. And in 1530 the first textbook on dentistry in Germany was published.

At the end of the Tudor period, Shakespeare makes a casual reference to teeth cleaning in a play. But barber-surgeons continue to practice their trade, if not a barber-surgeon, they can be a juggler followed by a tooth extracted to thrill the crowd.

The seventeenth century saw the French physician Pierre Fauchard lay the foundations for modern dentistry. He discarded concepts such as the tooth worm and published a book “the surgeon dentist”. One concession to former ways was the use of urine as a mouthwash. But among its many novelties with a cleaning, separation, removal of cavities, cauterization, filling, straightening and strengthening of teeth and the claim that sugar caused cavities.

The first dental textbook written in English was Charles Allen’s “Operator for the teeth” in 1685. And in the 1700s in Georgian England, dentistry was finding its feet as a profession. There were many developments, although some practices continued to include, yes, the use of urine as a mouthwash. A new practice was the use of gunpowder to clean teeth. They also used red-hot wires to cauterize the patients’ nerve endings. Fillings were an exciting development, although you are filling the choice with poisonous lead or beeswax which is the Neolithic solution.

Georgians also developed porcelain fillings, although unfortunately, the lovely white filling would tend to kill the tooth around it. If the tooth had to be stripped, there was always the possibility of a replacement carved from ivory or walrus tusks. Now many people seem to think that George Washington had false teeth made of wood, this is not true, and they were actually made with his own teeth, cow teeth and hippo ivory. Unfortunately, they were set in a metal mouthpiece with springs that fitted poorly and distorted the shape of his mouth.

In the late 1700s, the English prisoner William Addis is believed to have developed the first mass-produced toothbrush. In his cell, he was unhappy with simply rubbing a rag on his teeth. He saved a small bone from a prison meal, obtained bristles from a goat, drilled holes in the bone, glued them together, and there is a toothbrush.

After his release, Addis became very wealthy. During The 1800s, the first dental schools were opened with the oral health industry and a requirement for raw materials for a prosthesis emerged. Before porcelain teeth were perfected for dentures, they were usually extracted from the mouths of dead soldiers, often soldiers who fought in the American Civil War. They were used nationally and shipped worldwide by barrels.

The 19th century also saw the development of toothpaste in jars. And in 1892 dr. Connecticut’s Washington Sheffield was the first to put toothpaste in a collapsible tube. Urine-based pastes were no longer the only option, so the world of oral health and dentistry as we know it today began to take shape in the early 1900s.

This story sounds like progress, although recent research shows that over the past 10,000 years reduced diets and the pursuit of oral health have reduced the spectrum of bacteria in the mouth and have surprisingly contributed to chronic disease. Despite that, our summary of the archaeology of dentists has certainly given me a new perspective. My dentist is well trained, they work in a clean hygienic environment. Heck, I can brush my teeth with toothpaste, I don’t have to rely on stale urine.

ever enjoy going to the dentist.

This article is written using information available on the Internet. So some information is questionable. If you have any information on this topic please comment on it. (Like the post and share) 🌹🌹🌹